Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

It’s been several years since I wrote my last book, but it mattered to me at the time it was published whether or not it was noticed in important newspapers and magazines. I think I’d still feel the same way today, as would most serious nonfiction writers.

You write a nonfiction book because you want to be part of a larger conversation. You also expect that having it noticed by an outlet with a large and/or prestigious audience will help you sell a few copies.

At Sutherland House, we put considerable effort into gaining media coverage for our books. It’s one of the things we do best—better than most of the big houses, in fact. It helps that we publish a great deal of topical nonfiction, which appeals to the editors of newspapers and magazines.

It follows that we care about the state of the media. I also feel a personal stake in it because I spent much of my career at print periodicals and many people I care about are still trying to make it work in that industry or in broadcast. But, lord, the news about media has been awful of late.

Yesterday it was Bell Media dumping almost half of its radio stations and hundreds of employees. Last week, The Messenger, a high-profile and well-funded news start-up was shuttered, days after Business Insider laid off 8 percent of its staff and the Atlanticwrote this about the week prior:

For a few hours last Tuesday, the entire news business seemed to be collapsing all at once. Journalists at Time magazine and National Geographic announced that they had been laid off. Unionized employees at magazines owned by Condé Nast staged a one-day strike to protest imminent cuts. By far the grimmest news was from the Los Angeles Times, the biggest newspaper west of the Washington, DC, area. After weeks of rumors, the paper announced that it was cutting 115 people, more than 20 percent of its newsroom.

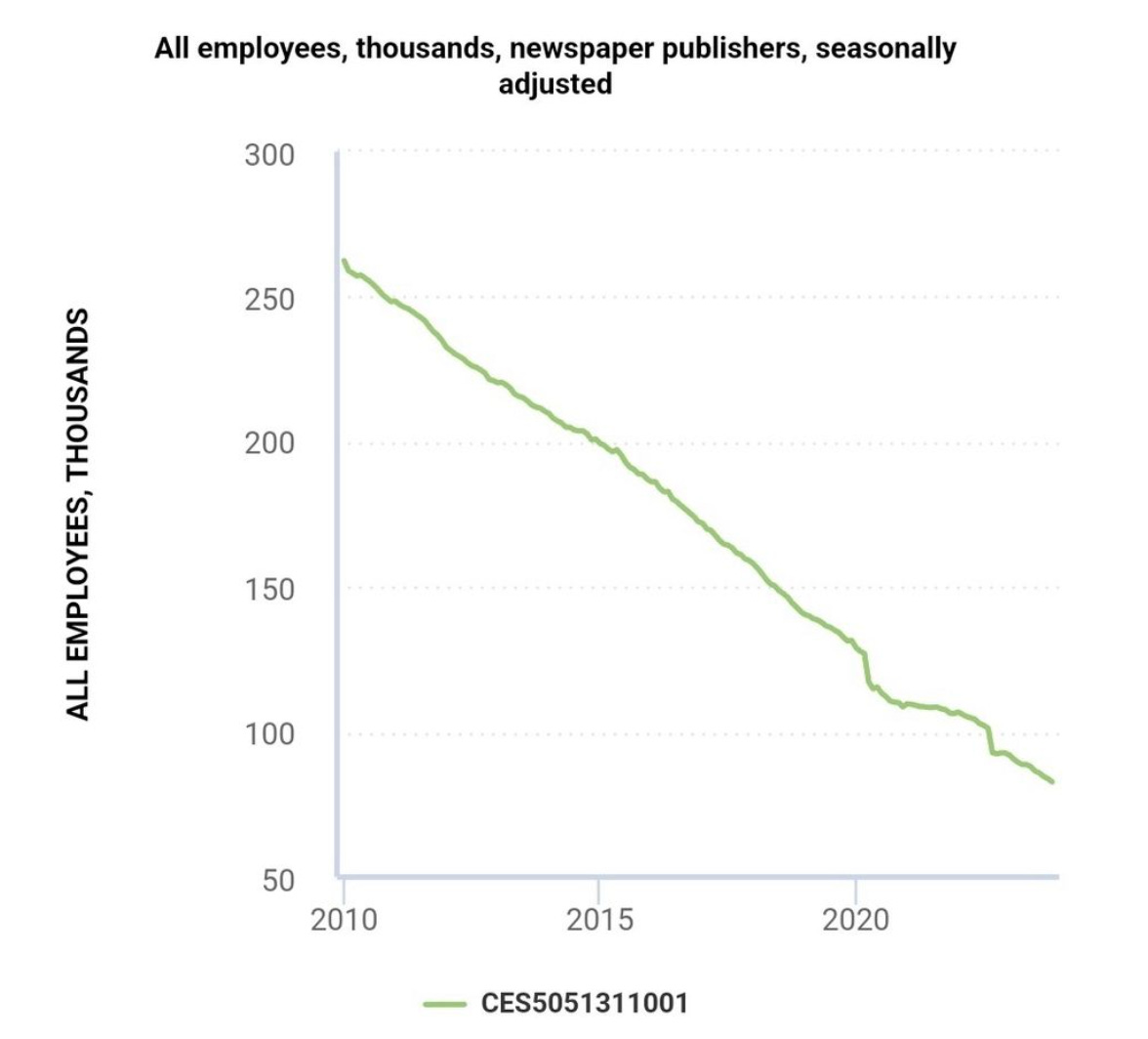

It’s been that way week after week. For years. For decades, in fact. Conventional broadcast outlets, magazines, and especially newspapers are disaster sites. From the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, total employment in the newspaper business:

I tend to be an optimist about emerging media, but digital has a long way to go before it comes close to employing even the low number of journalists the decimated newspaper industry currently employs. From the Pew Research Center:

Since those numbers were published, digital journalism has hit a rough patch. I would expect that an update of the above chart, extending from 2020 to 2024, would show declines for both newspapers and digital.

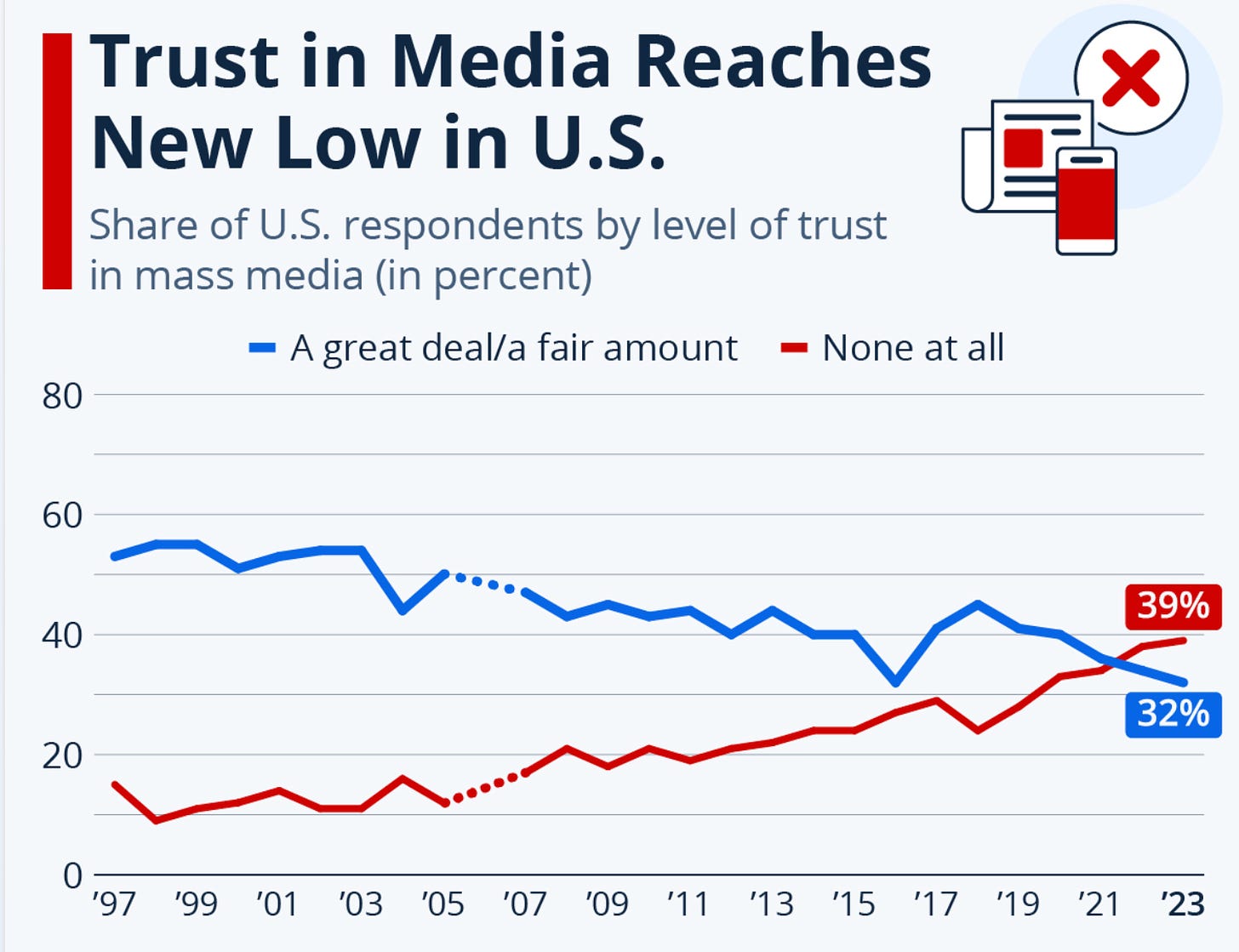

As depressing as those numbers may be, they aren’t the worst indicator of the state of media today. Gallup and the Knight Foundation last summer released a survey that found the following:

The survey took a closer look at the relationship between levels of trust in news and where the respondents were getting their news. The cable news environment—Fox, CNN, MSNBC—was associated with lower trust than either the old television networks (CBS, ABC, NBC) or such national publications as the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, in which two-thirds of respondents still showed moderate to high degrees of trust. Nevertheless, the situation is deteriorating across the board. Even surveys that find the distrust less pronounced than Gallup/Knight find distrust to be profound and accelerating:

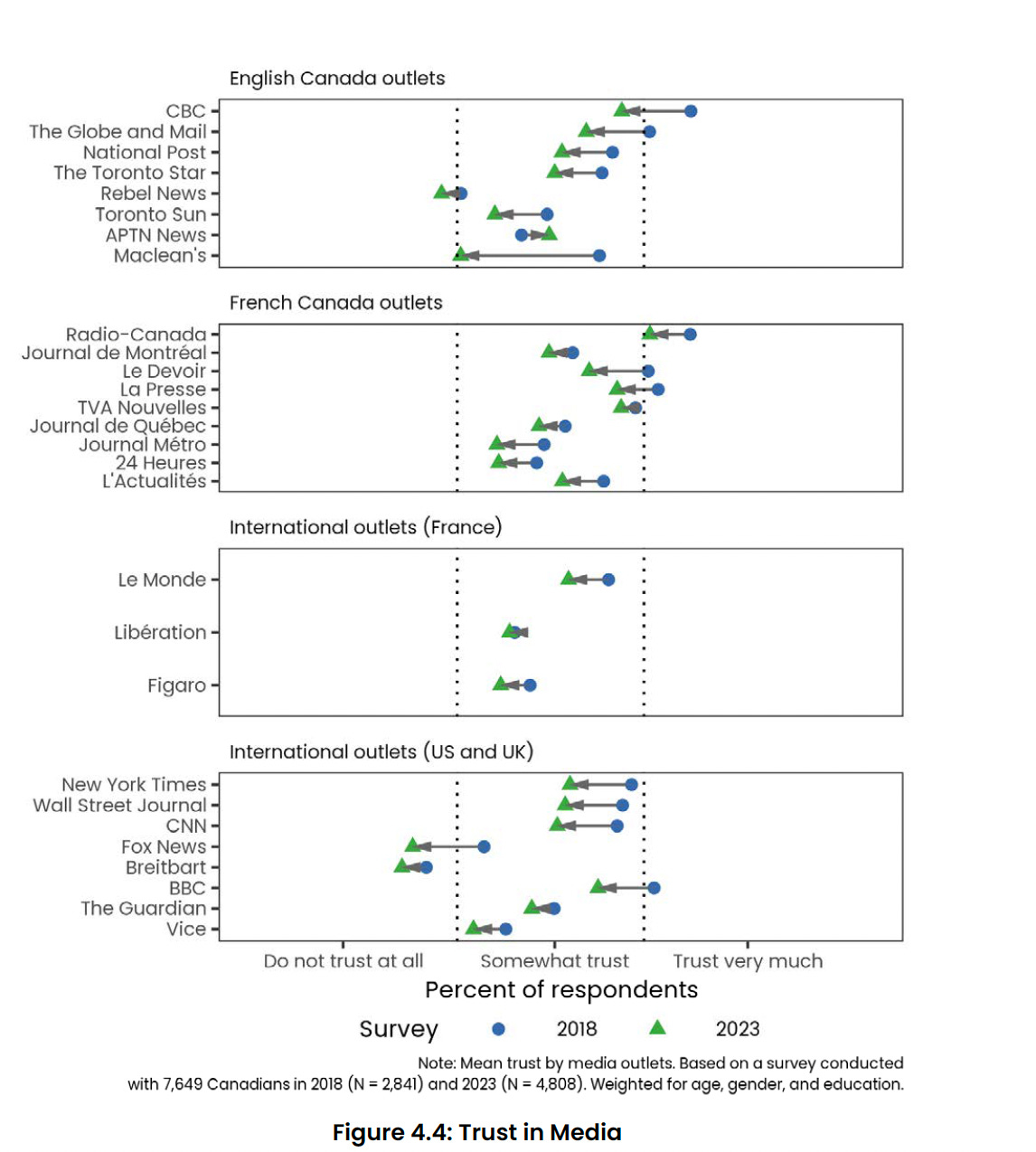

Good thing I live in Canada, you might be thinking. A few years ago, in the wake of the Capitol Hill riots, the CBC indulged in a bit of schadenfreude and reported on the decline in media trust as an American phenomenon:

Last year, McGill’s Media Ecosystem Observatory released a survey suggesting we’re kidding ourselves if we think we’re immune from these dynamics. Every one of the twenty-eight news outlets measured by the survey had fallen in the esteem of its Canadian audience over the last five years. Not a single English-language news organization in Canada is trusted “very much” today. Poor Maclean’s plummeted from quite respectable to the verge of “do not trust at all.” Radio-Canada is the only French-language serve that might be considered “very” trustworthy, and it’s right on the line with “somewhat” trustworthy.

The study’s authors, who obviously want to believe that an informed electorate is the beating heart of our democracy, placed at the top of their list of conclusions: “Most Canadians are inattentive to politics. On average, Canadians do not frequently consume news, have low levels of political knowledge, and have low awareness of important political figures in Canada.”

Where is all this headed? Adults aged eighteen to thirty-four get more of their news on social platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube than from conventional media. Over a nine-month period, Jordan Peterson, together with his daughter, Mikhaila, had four times the viewership of CBC—Canada’s most trusted news source—on Canadian YouTube:

You may wonder why would people in the book business would care about layoffs and financial problems at media outlets that aren’t trusted by the people for whom they’re intended.

It’s complicated. Different segments of the public, and especially people over the age of thirty-four, still tend to find conventional media at least somewhat trustworthy. And even if the audiences for those outlets are declining, they’re still large audiences by most standards. And their attentions tend to move books.

Outside of getting noticed by Reese Witherspoon, Oprah Winfrey, Jenna Bush, Bill Gates, Barack Obama, Joe Rogan, or a thousand teenagers on TikTok, conventional media remains the best publicity option we have. How much longer that will remain so is an open question.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )