Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

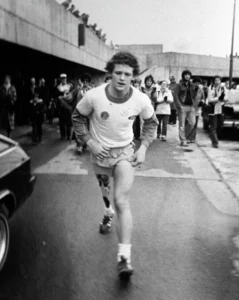

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter.

Barnes & Noble has been on death watch. It is down to 627 stores, having closed 400 over the last two decades, and it was bought this summer by a private equity firm for $683 million after having shed $1 billion in market value over the last five years. The hedge fund and a lot of North American publishers are hoping James Daunt can salvage this literary chernobyl because Amazon can’t have everything. Their hopes are not without foundation.

Daunt took over Waterstones, the largest chain in the UK (289 stores), when it was circling the drain in 2011. Waterstones has been reliably profitable since 2015. Daunt’s tricks? Apart from hiring people who like books and de-corporatizing the stores, he stopped taking money from publishers to stock their books and, as the Times says, filled his shelves with “books that customers actually want to buy, as opposed to the books that publishers are eager to sell.”

The big consequence of this approach was that Waterstones, which had been returning 20% of its inventory to publishers unsold, is now returning just four per cent of its books. That means more sales revenue and reduced costs (booksellers don’t have to pay for unsold books but they have to ship them back at their own significant expense).

The entire book industry wins when a big bookstore chain manages to restore its profitability reduce its returns. High levels of returns (up to 25% at Barnes & Noble) have been a huge frustration to publishers and booksellers alike. Every revolution has its victims, however, and this is where the New York Times article did not go.

Daunt likes to claim his approach to selecting books is more human and idiosyncratic than Amazon’s algorithmic methods, and that decisions about book ordering have been pushed down from head office to managers at individual stores. That may be true but UK publishers we’ve spoken to say the chain has reduced its returns by taking fewer chances and doubling down on predictable sellers. Some of the big multinationals are pissed that they can no longer muscle every title they produce onto Waterstones’ shelves. Some smaller publishers complain that it has been harder to get the chain to take a chance on their books in recent years.

We admire Daunt’s clear thinking and we share his faith in bricks-and-mortar bookselling — only five percent of Waterstone’s business is online. We hope he succeeds and that his practices spread throughout the bookselling community (high levels of returns are the worst kind of waste). There’s no question, however, that Daunt’s presence is going to tighten an over-supplied book market and that some North American publishers, and their authors, are going to find things a lot more challenging in the years ahead.

We are grateful to our friend Charit for this item. The Jaipur Literature Festival, an annual affair in the Indian city for which it is named, is the most colorful and, apparently, the largest free literary festival in the world. Tens of thousands of attendees come out to see 300-plus writers and thinkers. The British author William Dalrymple is one of its directors; the Indian writer and publisher Namita Gokhale is the other.

Anyway, the JLF has been travelling a bit in recent years to places like Houston and Adelaide. This fall it lands in Toronto’s Distillery District, which is a bit of come-down from the Hotel Diggi Palace where the original is held but still worth a visit.

Apparently Dalrymple himself is coming to promote his new book, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, published next month by Bloomsbury. It sounds like fun:

The Anarchy tells the remarkable story of how one of the world’s most magnificent empires disintegrated and came to be replaced by a dangerously unregulated private company, based thousands of miles overseas in one small office, five windows wide, and answerable only to its distant shareholders.

If you’ve not read Dalrymple, we agree with Charit that he is “quite pompous but writes well.” Charit also notes that Dalrymple’s earlier books on the Mughals and India are beautifully narrated. There’s a good interview with the author here.

This week’s question in our regular Ask a Publisher feature comes from Garnett: “What’s the best way for me to pitch my book to a publisher?”

Well, Garnett, there is no single correct way to pitch a book idea to a publisher. What works for fiction will be different than what works for cookbooks or narrative non-fiction. Our expertise is in the latter so what follows is an approach to pitching narrative non-fiction (defined as a true story with a beginning, middle, and end, intended for a general audience). The method was taught to me by a couple of top-flight agents who have landed thousands of books with the best publishers in New York and Toronto.

A pitch is not a single document but a package of documents including an introduction, a sample chapter, a chapter outline, an author biography, and a marketing sketch.

Let’s start with the easy part, the author biography. This is neither a curriculum vitae or a womb-to-tomb biography. It is a few hundred words designed to give a publisher confidence that you can execute what you are proposing. Include relevant literary experience, expertise pertaining to your proposed subject, previous publications, institutional affiliations (magazines, say, or universities), awards or other marks of distinction, praise from credible sources.

The purpose of the marketing sketch is to alert the publisher to anything you might be able to do to help sell your book, or any particular reason it might find an audience. Do you have a strong social media profile, or regular print or broadcast outlets? Do you do a lot of public speaking? Do you have any useful connections who will blurb or otherwise endorse or promote your work? Is your book pegged to an important event or an anniversary, is it genuinely newsworthy, or are there comparable books that suggest an audience for what you’re proposing?

The purpose of the sample chapter is to demonstrate your ability to write. Pick a chapter that will get a publisher interested in your subject, one that gives you an opportunity to show a command of style and narrative. It might be as short as ten or fifteen pages, or as long as forty or fifty. It might be front the start of the book or the finish. It might be the only chapter you’ve written. What matters is that it is compelling.

The purpose of the chapter outline is to demonstrate that you have more than one chapter in you — that you and your subject can carry a book of the length you are proposing. One solid paragraph per chapter should do it (although I’ve know writers to do a page per chapter). The paragraph should give the reader an idea of both the content of the chapter and how it fits in the larger story. Collectively, the chapter outline should tease out the principal characters, incidents, and themes of the book.

It is not necessary at the pitch stage to be certain about every character, incident, and theme you will treat in the book. Minds change and new information turns up in the course of research and writing. It is nevertheless helpful to project a strong sense of direction for your project. It may change as you do the work but projects that start off aimlessly tend to end that way.

Finally, the introduction. Its purpose is to grab a publisher by the lapels and convince him or her to buy this book on this subject by this person (you) right now. Why is the story interesting, important, original, topical? If it is not most of those things, you might consider another subject. This document need only be two or three pages long but it must sing and convince, and you should probably pay more attention to it than to any other part of the package. If a reader is not captivated by the introduction, the rest of the package might not matter.

New writers often ask how much work they should do before pitching a project. A benefit of the above approach is that it answers that question for you. If you can write a strong sample chapter, a thorough chapter outline, and a compelling introduction, you are probably deep enough into the project to know if it is real and worthwhile.

As we’ve mentioned in previous posts, you do not need an agent to send your pitch to a publisher. Many publishing houses, including this one, are happy to consider unsolicited proposals and manuscripts with or without an agent.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )