Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

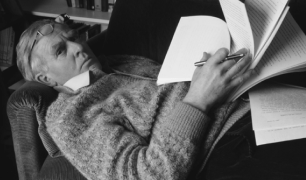

I’ve long believed the Nobel committee should bestow its laurel, at least once, on a genre novelist. Someone like Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, Anne Rice, Patricia Highsmith, JRR Tolkien, or Elmore Leonard whose work generally takes a recognizable form — say, the detective, horror, scifi, or romance novel — yet at its best transcends that form to rank among the very best works of world literature. My nominee is John le Carré, who died before Christmas at the age of 89. I was late to le Carré (David Cornwell). I’ve never been a fan of spy novels. I rolled my eyes the first time I read that Philip Roth considered A Perfect Spy to be the greatest British novel since the Second World War. Better than Ishiguro? Graham Greene? Anthony Powell? Iris Murdoch? Another dozen names flashed to mind. It was impossible. I was slow to Roth, too, after reading that.

The 1950s and 1960s brought a string of stunning revelations of well-born, well-educated Brits serving as Soviet agents. The likes of Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Kim Philby. In le Carre’s hands, these defections provided a template through which to address British decline in the post-war period, a time of real distress in the U.K, made especially unpalatable for the conspirators by the fact that the U.S. and the Soviets were meanwhile racing ahead for global domination and the heavens. Writes Wilson:

The British could not afford spaceships and rockets. The Union flag was never going to be planted on the moon, but in the ideological conflict between big clumsy market-led democracy and big brutal Marxist-Leninism, a certain breed of British could indulge in skills which they had perfected at their public schools: double-think, lying and treachery.

The double-think is especially important if we are to understand the spies, and the creepy-silly-undeveloped-schoolboy world they inhabited.”

All of this is uniquely captured by le Carré, writes Wilson, and something more: “The resentment at the loss of British power in the world fed into a hatred of America, which derived real satisfaction from the notion of joining forces with the only power in the world which could at that date plausibly challenge the military muscle and political influence of Washington.” That was enough to get me to try A Perfect Spy, which may well meet Roth’s estimation (which has since been echoed by Ian McEwan, one of the best British novelists now writing). And from there I became a convert and read le Carré’s whole shelf.

Wry, dryly funny, patrician, a great mimic, a seasoned anecdotalist, handsome into old age, his spoken sentences as beautifully constructed as his written ones, a lover of the crystalline prose and perfect plotting of P.G. Wodehouse, Mr. le Carré charmed the armies of interviewers who came to his cliff top house in Cornwall, where he liked to go for long walks. (He lived part-time in Hampstead, London, but avoided the literary social scene.) Spies came to visit, too, treating him like a kind of oracle for their own profession.Anthony Lane in the New Yorker had some fascinating things to say about le Carre’s craft:

What set le Carré apart, gave him his edge, and kept it whetted from one decade to the next was his forensic skill. Ideas and passions, under his guiding hand, are never floated; they are tethered down and incarnated in his characters—in their particular speech patterns, and in the inch-by-inch inflection of their movements.Investigative reporter Jeff Leen wrote in the Washington Post of introducing le Carré (“David”) to his sources in the Miami drug world, and of the author’s research methods and powers of observation:

David was not so interested in the tech, the calibers or the weaponry. “That’s easy to get, and I can fill that in later,” he told me when we were alone. He wanted the feel of the relationships between the characters, the casual talk, the unexpected detail that resonated or revealed new depths. After one meeting with a powerful senior agent, David remarked on the man’s “dorsal muscles,” and how they revealed his inner tension, power and control, all in conflict and all finely balanced, as if on a knife’s edge. Another time David pointed out that one agent he had just met really disliked another at the meeting, his boss. It was all communicated through the body language, the tone and the silences that hung in the air. It was only years later that I saw the enmity between them emerge and I realized David had been right.The best and truest quote about the novelist I’ve read over the last month was from Timothy Garton Ash two decades ago in the New Yorker:

Thematically, le Carré’s true subject is not spying. It is the endlessly deceptive maze of human relations: the betrayal that is a kind of love, the lie that is a sort of truth, good men serving bad causes and bad men serving good.I’d second that and go a bit further. John le Carré was a chronicler of the crisis of human identity that befell the Western World towards the end of a tumultuous and ruinous century, and that remains perhaps the most vexing problem of our times. Not incidentally, his prose stands with any of his contemporaries’ for economy, clarity, precision, and fluidity. A true master. He’ll never win the Nobel — although he’s at least as deserving as Dylan — but he doesn’t need it. And he might not have wanted it. From the NY Times: “He said he would never accept a knighthood or other state honor, though there were offers. ‘I don’t want to be Sir David, Lord David, King David,’ he said. ‘I don’t want any of those things. I find it absolutely fatuous.’”

So you want to make it as a singer-songwriter? Kat Goldman has been there, almost to the very top, and now she’s back with sage advice and hilarious behind-the-scenes stories from a lifetime of toil in the dive bars and legendary venues of the contemporary music scene. Learn what it\’s like to meet your first fan, date a rock star (never again!), perform in a grocery store, and rebuild your career after getting hit by a car in a bagel shop. Feel the sting of rejection and rampant sexism, and the thrill of writing a hit song and performing with your idols (if, sometimes, only in your imagination).As an intro, it doesn’t do Kat justice. She’s released several albums. She’s won songwriting competitions. She’s toured. She’s played The Bottom Line, the Bitter End, and the Living Room. She’s opened for Regina Spektor and Dar Williams, the Waifs, the Strawbs, among others. Her songs have received good radio play and television exposure, and they’ve been covered by many other artists. She didn’t fail in music. She did a lot of great things. She just happened to throw everything she had into a fickle business that never seems to repay what performers put into it. And now she’s doubling down on that error by becoming a writer. In a pandemic, when she won’t be able to see her book on a bookshelf (not for months anyway), and she won’t be able to celebrate in the presence of other people. Nor will she be able to promote the book with live people. We’d envisioned Kat promoting the book with a series of concerts/readings at bars/bookstores in Canada and the US. Instead, there’s this:

Maybe that’s because it’s not out yet, but it’s not in the ‘coming soon’ category either. I checked the site’s news feed. There’s a story about a Sally Rooney novel coming out next fall. Another about forthcoming book from Senator Murray Sinclair. Another on the death of John le Carré. And no less than four on the company’s “anti-racism action and accountability” plan. Not a peep about JPB.So I used the search feature on the site, which led me to the book’s page. It doesn’t seem that a lot of work went into the cover (above). It’s identical to the last one, except black rather than white. Peterson’s author page is just like every other author’s page, except skimpier. Almost all have a “praise section.” Not his.There’s also mention of Beyond Order in the Random House Canada spring catalogue, where it is the fourth of eleven titles arranged in alphabetical order. Nothing marks it as the book likely to ensure another round of fat bonuses at PRHC. It’s shaping up to be the most grudging launch in the history of blockbusters.

Maybe that’s because it’s not out yet, but it’s not in the ‘coming soon’ category either. I checked the site’s news feed. There’s a story about a Sally Rooney novel coming out next fall. Another about forthcoming book from Senator Murray Sinclair. Another on the death of John le Carré. And no less than four on the company’s “anti-racism action and accountability” plan. Not a peep about JPB.So I used the search feature on the site, which led me to the book’s page. It doesn’t seem that a lot of work went into the cover (above). It’s identical to the last one, except black rather than white. Peterson’s author page is just like every other author’s page, except skimpier. Almost all have a “praise section.” Not his.There’s also mention of Beyond Order in the Random House Canada spring catalogue, where it is the fourth of eleven titles arranged in alphabetical order. Nothing marks it as the book likely to ensure another round of fat bonuses at PRHC. It’s shaping up to be the most grudging launch in the history of blockbusters.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )