Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

From the desk of Sutherland House president Ken Whyte…

As regular readers know, I’ve been complaining here and there about the Canada Council for the Arts’ unilateral decision to not fund researched non-fiction and give all its money to fiction, poetry, and memoir. The two questions I get most often in conversations about the council’s actions are these:

1) Is there any legislation, or are there any published policies that explain the council’s choice to support imaginative literature and not factual literature?

2) How would you make the case that researched non-fiction is, in fact, art?

On the first point. As far as I can tell, the Canada Council has never formally investigated and/or explained its non-fiction decision, but the decision is clearly stated in the council’s glossary of terms. It defines literary non-fiction as work that presents “a text of personal reflection where the point of view and opinion of the author are evident. Eligible titles have a literary style and use narrative techniques. They must make a significant contribution to literature, the appreciation of works by Canadian authors or artists or knowledge of the arts.” And that’s what gets funded today. The definition goes on to say that joke books, calendars, guidebooks, cookbooks, how-to books, coloring books, collections of letters, and self-help books are not literary and get no support.

I’m not sure I’d out-of-hand dismiss guidebooks, cookbooks, collections of letters, and even some things that might be classified as self-help but let’s leave that for another day. I’m more concerned with other branches of non-fiction that don’t fit the council’s narrow definition of “literary”: works of history, biography, natural science, philosophy, religion, politics, criticism, and any other researched non-fiction that intends something other than personal reflection in a self-consciously literary style. These categories are simply ignored in the council’s stated policies, and they aren’t welcomed by the council in practice. A publisher who does a lot of history, politics, and biography sought clarification on these points and was told by a council officer: “We don’t like fact.” A recent Canada Council juror received instructions that any non-fiction written in the third person was ineligible for support.

So as far as the council is concerned, a writer disqualifies himself from granting consideration by choosing to base his work on fact rather than on imagination or personal experience, and by putting his story and his learning front and center, rather than himself.

Is there anything in the legislation that created the Canada Council that supports this narrow definition of art?

No.

The council is a child of the 1949 “Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences,” known ever since as the Massey Commission, after its chairman Vincent Massey. The commission’s final report (1951) recommended as follows:

That a body be created to be known as the Canada Council for the Encouragement of the Arts, Letters, Humanities and Social Sciences to stimulate and to help voluntary organizations within these fields.”

It is abundantly clear in the voluminous record of the commission’s proceedings that its members were concerned for the full range of literature: fiction and non-fiction, imaginative and scholarly. They were certainly not afraid of fact. (They also recommended the expansion of public records collections and the Public Archives of Canada, as well as historic sites and monuments, and museums.)

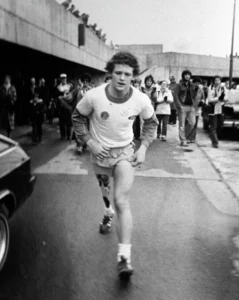

The section on literature in Massey’s final report makes room for the work of scholars, intellectuals, and critics as well as novelists and poets. It sees value in creative and interpretative work. It presents statistics on publications of fiction and “general non-fiction” to make its case for arts funding. All of this is consistent with the Massey Commission’s larger objective of advancing the whole of intellectual and cultural life in Canada (Massey, in his ridiculous vice-regal uniform above, himself being a man of letters in the broadest sense).

The 1957 legislation that flowed from the Massey report and created the Canada Council takes a similarly expansive view of the task. It expressly includes in its definition of eligible activities “architecture, the arts of the theatre, literature, music, painting, sculpture, the graphic arts and other similar creative and interpretative activities.” Literature is included without limits or qualifications. Both creative and interpretive works are expressly welcomed. The inclusion of architecture is further evidence of Massey’s accommodation with facts.

So there is nothing in the letter of the legislation or the expressed intentions of the legislators that argues against researched non-fiction. The choice has been imposed by the bureaucrats who run the Canada Council. And it is a consequential choice.

If the council considers a particular genre of literature to be artistic, works in that genre will qualify for grants, and the energies of the nation’s writers, publishers, and readers will tend to follow. If the council determines that a particular genre does not qualify as art, the realities of the publishing business in this country dictate that the genre will wither, especially when the creation of such work is expensive.

We shouldn’t want to see our factual, researched-based literature wither at a time when the world is finding it especially difficult to keep a grip on fact and truth.

2) I’ll be quick on this one. One has to be uninformed, or uneducated, or otherwise obtuse to miss the artistry in first-rate researched non-fiction. A talented author will write clear and elegant prose and use the full resources of the language. She may write with charm, anger, humility, audacity, curiosity, vivacity, or wit—these things can survive the resort to the third person. She will deliver a well-structured narrative, precise detail, vivid scenes, and apt metaphor, and develop themes, perhaps using antitheses and shifting points of view. There are few tools available to the novelist that cannot also be employed by non-fiction writers.

There are other stylistic elements of special importance to the art of researched non-fiction, including applied knowledge, depth of research, marshaling of fact, quality of analysis, soundness of argument, originality of insight, intellectual purpose, and the ability to give pleasure without compromising truth.

There is no legitimate case to be made for dismissing researched non-fiction from granting consideration. The Canada Council (I hope) would never disqualify photography because it reflects observable reality, or sculptors because they work within the limits of their materials.

Style, per Proust, comes down to a quality of vision, and while a biographer or a historian or a science writer might choose to keep that vision in the background, along with the authorial presence, it is nevertheless discernable to a sensitive reader. Anyone who reads widely in non-fiction will appreciate stylistic differences and the varying degrees of artistic merit among authors. It takes effort to miss them.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )