Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

[row v_align=\”middle\” h_align=\”center\” depth=\”4\”] [col span=\”6\” span__sm=\”12\”]

how a handful of Oxford twits led by Boris Johnson took over the United Kingdom and engineered Brexit. This indisputably happened, and the book does a reasonable job of charting how, while providing a running commentary on privilege in the UK, the dominance of Oxford in the cultural and political life of the nation, and what absolute shits Johnson and his buddies were as young men.

[/col] [col span=\”6\” span__sm=\”12\”] [ux_image id=\”18825\” image_size=\”medium\”] [/col] [/row]

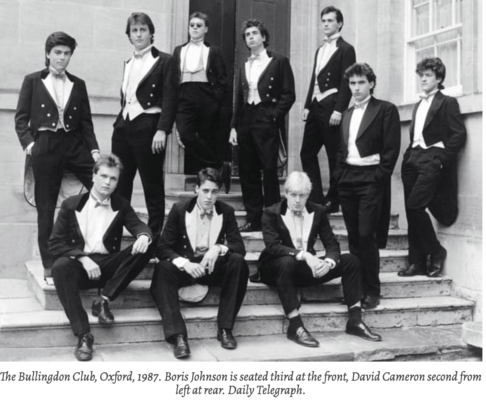

Johnson arrived at Oxford from Eton, where his yearbook photo showed him posing with a machine gun alongside an inscription pledging him to register “more notches on my phallocratic phallus.” He joined the all-male Bullingdon dining club and posed with some of its exclusively upper-class members (among them another future prime minister, David Cameron) for the photo above, which, believe it or not, was an emblem of Cool Britannia in the Blair years. Writes Kuper:

\”The Bullingdon was defiantly anti-meritocratic: almost all of the members were selected on the basis of their social origins and gender. It specialized in public statements of entitlement. Club members went around in a pack sacking restaurants or the rooms of new members, smashing bottles in the street, humiliating hired sex workers, and ‘debagging’ (removing the trousers\’) of lower-caste outsiders.\”

Johnson spent much of his time at school conniving his way to the presidency of a debating society, the famed Oxford Union. An American who observed him in action reports:

\”Boris was an accomplished performer in the Oxford Union where a premium was placed on rapier wit rather than any fidelity to the facts. It was a perfect training ground for those planning to be professional amateurs. I recall how many poor American students were skewered during debates when they rather ploddingly read out statistics; albeit accurate and often relevant in their argumentation, they would be jeered by the crowds with cries of ‘boring’ or ‘facts.’\”

On it goes, with Kuper ultimately blaming the deplorable character of Johnson and his Oxford set for accomplishing Brexit and ruining Britain. You don’t have to agree with the author that they rank on a par with the traitorous Kim Philby and the 1930s Cambridge spies to enjoy the book. [ux_image_box img=\”18829\” image_width=\”49\”]

by Simon Kuper

[/ux_image_box]

What I appreciate most in Chums is its insight into British journalism. Johnson started his public career as a hack for the Telegraph and the Spectator (after getting fired by the Times for making up quotes). Both of those publications were owned in the nineties by Conrad Black and Hollinger Inc. (I ran into Johnson once or twice in my capacity as a North American Hollinger hack. He impressed as the most assiduous of Black-asskissers, and he would be the first to turn on him when the SEC knocked.) Kuper, another hack (Financial Times), traces a dominant style of British journalism, one at which Johnson excelled, to Oxford and the Oxford Union.

If you’re North American, you can’t read far in British newspapers and magazines without being impressed at the degree to which rhetoric trumps substance. It’s an approach best exemplified by the off-hand, fact-light, ironic banter of The Spectator, briefly edited by Johnson, but even high-minded writers at more serious publications such as the Financial Times and The Economist strive for similar effects, as though eternally frightened of being jeered with cries of “boring” or “facts.”

Oxford graduates have long been over-represented in British journalism, filling leadership roles from The Guardian to the BBC to the Economist and the Daily Mail. As students, writes Kuper, they are taught to advance bold, preferably counter-intuitive propositions as provocatively and succinctly as possible. That is standard Oxford essay style, and it is reinforced by the Union where debaters aren’t expected to know their shit or believe what they\’re saying or care about nuance or consequences: it only matters that they’re interesting or charming and supremely confident (of, if you prefer, glib and flippant), preferably with a ruling-class accent.

That is rhetorical skill so far as Oxford and UK journalism are concerned. Something like the New York Review of Books, with its long footnotes and tedious paragraph-by-paragraph mounting of arguments, would never fly.

As Kuper admits, the Oxford approach is not all bad. It can be bracing and enjoyable to read (as Johnson was at his best). And we must admit that North American journalism, left unattended, slides to dreary and didactic. We benefit hugely from occasional jolts of Oxford sensibility from the likes of Tina Brown and Nick Denton (both Oxford), not to mention the brilliant Armando Iannucci (Veep and The Death of Stalin) and John Oliver (although he’s Cambridge).

As with everything, there are limits. Unadulterated charm and cynicism produce a tedium of their own. And elevating the likes of Johnson from a debating floor or newsroom to a position of real power is not without risk.

I’m no longer the world’s biggest crank on public libraries. My argument, you’ll recall, is that public libraries are a good thing, but that North Americans borrowing rather than buying three out of every four books they read is a bad thing for the incomes of authors, the economics of publishers, and the welfare of just about everyone else involved in the book industry. That’s fainthearted stuff compared to this week’s tweet from Chris Freiman, a philosophy professor at William & Mary:

As you can guess from the 4,152 comments he’d generated by last night, Freiman’s was an unpopular take. Summing up the responses:

No one has been in a mood to ask if Freiman has a point, or where he’s coming from. For what it’s worth, he has a track record of criticism of government welfare spending. His usual schtick is to ask why so many Americans are poor when the poverty line for a family of three is $18,530 (annually) and welfare spending on a family of three from all three levels of government amounts to $61,830 (annually). It’s not the worst question.

His answer appears to be that directly transferring funds to the poor would be a more effective and efficient way of alleviating poverty than allowing governments to keep running expensive programs that are failing to achieve the same end. That’s not the worst answer.

But does he have a point regarding libraries?

I give him half a point. Public libraries are overwhelmingly used by people who can afford to buy books, and those people are reading primarily for pleasure. I’m all for lending books to people who can’t afford them, who have trouble accessing them, or who want to improve their minds by reading important or serious stuff. But to the extent that libraries are giving middle-class patrons free entertainment—sure, privatize them. There are better uses of public money. Apply the funds to reduce tax burdens on low-income families or improve conditions in government-run nursing homes.

Where the privatization argument fails is that libraries do a lot more than provide middle-class patrons with entertainment. They are important community hubs and for a minority of users they continue to fulfill their original purpose, which, says historian Ed D’Angelo, was to “promote and sustain the knowledge and values necessary for a democratic civilization.” Privatization would likely destroy the valuable public service aspects of public libraries.

In fact, the real problem with public libraries today is that they’re already half privatized. Starting in the middle of the last century, they stopped believing in their role as the community’s edifier-in-chief. They adopted the mindset of the marketplace, giving people what they wanted, filling their shelves with multiple copies of the hottest bestsellers, however vacuous, and measuring their success by counting foot traffic at their branches. They now manage those branches like Walmart supercentres, maximizing transactions per square foot of space. Who cares what patrons are reading, or why, so long as the turnstiles are spinning.

I’d prefer they leave private-sector thinking to the private sector, and let public libraries rebuild their lending practices around their original mission of elevating the minds of citizens. Surely we can’t yet afford to abandon the latter objective.

My solutions to the public library problem, in order of preference, are a much more robust public lending right, an exclusive new release window for the retail trade, and user fees for patrons who can afford them. More discussion here.

In any event, thanks to Professor Freiman for revealing me as a moderate.

[row] [col span=\”6\” span__sm=\”12\”] [ux_image id=\”18833\” image_size=\”medium\”] [/col] [col span=\”6\” span__sm=\”12\”]Author and regular SHuSH correspodent Roy Macskimming writes in response to a comment about Jack McClelland (above) in SHuSH 150:

As one of countless fortunate readers and many fortunate authors who benefited from Macfarlane Walter and Ross

and its high-quality publishing, I\’m happy to read your admiring tribute to that firm. Jan Walter took on The Perilous Trade, my study of Canadian book publishing, and Jan\’s commitment and editorial work made it a better book. Alas, MWR was shuttered just before the book\’s release, and it appeared from McClelland & Stewart.

I also enjoyed your encomium to John Metcalf, a great editor in his own right and a very fine writer. A read of The Perilous Trade\’s two chapters on Jack McClelland will show that John, however, has got Jack wrong.

It\’s fine for John to say the reputations of M&S and Jack himself are overblown. That\’s his opinion. But to write that Jack was \”less Max Perkins, more Barnum & Bailey\” misses the point of Jack\’s and M&S\’s indispensable importance to Canadian literature. Perkins was a brilliant editor, working within an already storied and prestigious firm, Scribner\’s. Jack was a brilliant publisher, who took over the reins at M&S and made it the predominant and most influential Canadian firm of the 1960s and \’70s. At its height, M&S published more important Canadian authors than anyone else, and Jack personally made sure they were promoted with tremendous flair, sometimes circus-like but always memorable. Jack\’s legendary panache was badly needed in the country\’s tame literary culture of the time.

Unlike Perkins, or for that matter John Metcalf, McClelland was running a business. He struggled to keep it not only highly creative but financially viable and staked his soul on the outcome. As The Perilous Trade describes, Jack made plenty of mistakes and eventually ran out of rope. But he dared greatly, inspiring many of his employees, including Jan Walter, Anna Porter, Jim Douglas, Scott McIntyre, Alan MacDougall and Mark Stanton to start up their own exceptional publishing houses. Canadian book publishing would be unrecognizable without him.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )