Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

Like most of my peers in journalism, I started out with dreams of where I would work and the stories I would cover and the career I would have. I don’t think it occurred to any of us, even those much younger than me, that someday the whole business might shrivel and die, leaving us stranded in a world that no longer recognizes or requires our particular skills.

It happens.

While a few stalwarts remain in the desiccated industry, still somehow managing to do good work, most of us have moved on. Some back to school. Some to real estate. Many to communications.

At least one thought it wise to leap from a dying field into a related field that is probably dying, although it’s difficult to tell for sure or, at least, at what rate.

But nobody made a leap quite like Jason Logan’s.

I worked with Jason for most of a decade at Maclean’s, starting in the Aughts. I was editor and he was art director, primarily responsible for our covers. I loved working with him. When I first met him, he had a business card that held contact information and one message: “Works well with others.” It was one of his most notable characteristics, but he had many. He was smart, funny, incredibly talented, and he brought a child-like joy and enthusiasm to his work that withstood pretty much everything I threw at him. He was as genuine a person as you’ll meet. And now he’s a movie star.

After Maclean’s, he served as creative director for all of Rogers Publishing and after that for the Metro newspapers, a position that lasted until 2021. Along the way, in 2013, perhaps reading the writing on journalism’s wall, perhaps because he was never entirely reconciled to industrial-scale media, he started a little something called The Toronto Ink Company.

He makes ink.

It’s funny. Ink has been my primary medium for most of my career and I‘ve never spent three minutes thinking about it. I’ve thought a lot about paper—it’s size, texture, weight, cost—but I’ve always taken ink for granted. The ink that produced my work was the ink necessary for the large presses that printed newspapers, magazines, or books. I was never consulted about ink and it never once came up in all those years of conversations about publications, their design and manufacture. When it comes to writing on paper, I prefer pencils (Tombow Mono, 2B).

Jason thinks hard about ink. He doesn’t make the stuff used on big presses—heavily processed inks with all their varnishes, resins, solvents, waxes, and lubricants. He forages around Toronto for natural pigments that he combines with food grade Indian shellac and Canadian Shield wintergreen. He calls them “street-harvested pigments.” They have names like Sumac, Tumeric, and Black Walnut.

The Colour of Ink is a new National Film Board feature directed by another Maclean’s refugee, Brian D. Johnson. It is ninety minutes about Jason, his obsession with ink, and the artists around the world who share the obsession and his ink.

You learn a lot about ink in the film. For instance, that you can make it out of almost anything. Roasted peach pits. Crab apple blossoms. Rust. Desert salt. Copper wire. Rail spikes. Wild grapes. Snails. Dandelions. Buckthorn berries.

You learn that the simplest, oldest form of ink comes from a type of soot known as lampblack. Add a little water, bind it with gum arabic (from the Acacia tree), and you get what Jason calls “the most silky, satisfying, pure black.” This is the ink used on papyrus by the ancient Egyptians and the first ink used in China around the same time.

Later you learn that lampblack ink isn’t actually the oldest ink. The earliest evidence of ink is etched into the mummified body of Ötzi the Iceman who in 1991 was pulled out of an Italian glacier after a 5,300-year nap. Ötzi has sixty-one tattoos, seemingly aligned with acupuncture points. His ink appears to have been made from burning wood or bones. (It’s not really the world’s oldest, either, given that octopi have been manufacturing the stuff for 300 million years.)

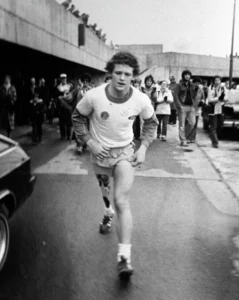

You learn all this in the film, but mostly you learn about Jason (above). He appears as he always does. I’ve never seen him in anything but jeans, usually with a simple t-shirt, and he travels everywhere in the city by bicycle. Tall, thin, with a lot of messy hair. Inky fingers.

You hear about his unusual personal history: he grew up in a kind of commune, the son of a manic-depressive hippy Christian minister; his mother died of Hodgkin’s when he was nine, the whole thing captured on film. Somewhat to his consternation, Jason’s former girlfriend, Katrina Onstad, lifted his story for her first novel, How Happy To Be. (That last part isn’t in the film).

He got interested in ink when he was twenty-years-old, living in New York and working as an illustrator for the New York Times. “I used to get all my supplies from a place called Pearl Paint, which doesn’t exist anymore. And in that store I found this bottle of black walnut ink and to me it was this absolute revelation that ink kinda grows on trees. Fast forward twelve years, I’m living in Toronto and my first child was born, and I got really interested in non-toxic ink. And I was on my way to work through Queen’s Park and I saw a little label on a black walnut tree and I thought maybe I could make my own black walnut ink.” That’s also the origin story of The Toronto Ink Company. It’s narrated with footage of Jason riding his bicycle through Queen’s Park and stopping beside the black walnut tree.

He\’s since made ink out of all the materials mentioned above and more. He sends his ink to artists he likes to see what they’ll do with it. Robert Crumb. The New Yorkercartoonist Liana Finck. Some guy named Koji, a master Japanese calligrapher who works on a heroic scale with brushes the size of mops. You meet some of these people in the film, along with an Indigenous artisan in Mexico who milks purple ink from snails and a tattoo artist in California who only works with the blackest blacks and covers acres of skin at a time.

They all share an appreciation for the natural ingredients Jason uses, not only things plucked from trees or bushes but stuff scraped from old bricks, the charred remains of wildfires, and rusted chunks of rebar. They like that his inks are rooted in place and that the non-carbon varieties are unstable. They move differently than printer’s inks and can change colour and consistency over time. Jason calls them fugitive. Others call them alive.

As a film, The Colour of Ink is rather messy, if we’re honest, although it’s hard to go wrong with a story that follows the genuine obsession of an intelligent person.

Coming away, I was mostly struck by a slightly reactionary thread running through it. Jason talks of his time in glass towers working on glass screens, producing often ephemeral work. He mentions how bits and bytes are so much less satisfying and durable than ink on paper. Similar sentiments are expressed by others. Liana Finck calls the handmade inks they work with “the opposite of digital ink.”

It’s a refuge, then, this community of ink. A return to the human scale, more substantial materials and sincere values. A world in which you not only direct your own very tangible work but own it. It made me happy to see Jason thriving in it.

He doesn’t seem to miss his former life. At the same time, he doesn’t seem to regret it. He learned how to maneuver in the glass buildings and he now uses those skills to produce custom inks for vodka companies and other corporate interests as well as for artists and illustrators.

“I’m the Ink Guy,” he says. “That’s my life now.”

I wish I could tell you where to see the film. It was released March 24 and ran for a couple of weeks in a number of cinemas across the country but is now off screen and awaiting a distribution deal. You can see some of Jason’s work here.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )