Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

We’re now into the fifth year of SHuSH and over that time we’ve had very little to say about North America’s second most important book publisher, HarperCollins. Now that the company has arrived at a critical moment—Rupert Murdoch is retiring as head of News Corp, the entity that owns HarperCollins—we should catch up.

At just under $2 billion in annual revenue, HarperCollins is substantially smaller than Penguin Random House ($3.3 billion), and substantially larger than the other three members of the Big Five—Hachette, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan. It operates in seventeen countries, including Canada, and has 120 imprints, among them William Morrow, Mariner, Avon, Harlequin, and Zondervan, a Michigan-based Christian publisher that sells more Bibles than anyone in the world.

(We never talk about the Christian market in trade publishing circles, but we should. They are the foundation of Western book publishing. Many long-lived, now secular publishers and printers began as godbotherers. Each of Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, and Simon & Schuster today depends on religious imprints to maintain its bottom line. Faith sells. Zondervan’s website offers 494 separate products under the Bible heading, dozens retailing for over $100.)

In addition to its Christian stream, HarperCollins has a powerful backlist featuring Harper Lee, Agatha Christie, George Orwell, J.R.R. Tolkien, Joan Didion, and Frank McCourt. Some of its faith-oriented authors—C. S. Lewis, Martin Luther King, Billy Graham—are big contributors to that backlist. The company’s bestselling contemporary writers include Daniel Silva, Karin Slaughter, Dave Grohl, Lucy Foley, Mitch Albom, and the Freakonomics guys. HarperCollins doesn’t have the literary cache of Penguin Random House but it has published some highly regarded authors, not least Joyce Carol Oates, Annie Dillard, Edward P. Jones, and Anthony Doerr.

HarperCollins is a minor asset in the Murdoch empire. The empire has been divided in recent years. There is a lucrative TV company, Fox Corporation (revenues $14 billion), which includes Fox News and Fox Sports. And there is a not-as-lucrative dead tree company, News Corp (revenue $10 billion), whose major assets are the Wall Street Journal, England’s The Sun and The Times, HarperCollins, and an odd digital real estate business that’s made up for much of the decline in News Corp’s newspaper revenues over the last decade.

All of these properties were one until the spectacular 2011 News of the World royal phone hacking scandal, which landed an editor in jail and smoked the reputations of several Murdoch newspapers. The print properties were spun off into News Corp to protect the television properties from potential legal and financial risks. (The television properties have since managed to find plenty of legal and financial risk of their own, particularly in the Dominion Voting lawsuit.) Last year, Rupert mused about reuniting Fox Corporation and News Corp into one empire but couldn’t get his shareholders to agree.

News Corp assets have not been neglected in the interim. Murdoch paid $420 million to purchase Harlequin from Torstar in 2014 and merge it with HarperCollins. He shelled out another $349 million to purchase Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2021.

The ninety-two-year-old Rupert is stepping down as chairman of both Fox Corporation and News Corp next month, leaving everything in the hands of his eldest son, Lachlan. Rupert will stay on as chairman emeritus and he’ll still control the Murdoch family trust, with its lock on 40 percent of the voting shares in Fox and News Corp. It is unlikely, then, that much will change in the Murdoch universe until Rupert assumes room temperature. It may not be long. While he claims robust health, Vanity Fair reports he has been “secretly hospitalized in recent years for a broken back, seizures, two bouts of pneumonia, atrial fibrillation, a torn Achilles tendon, and COVID-19.”

Who is Lachlan Murdoch? According to The Successor: The High Stakes Life of Lachlan Murdoch (2022), an excellent biography written by Australian business journalist Paddy Manning and published in North America by none other than Sutherland House, he is a fifty-two-year-old son of a billionaire, a graduate of private schools and Princeton, who has apprenticed to the family business most of his adult life. He’s into sailing and motorcycles. He married a television personality. They own the biggest mansion in Los Angeles yet spend most of their time in their native Australia. He fights with his siblings—two sisters and one brother—who many expect will turn on him the moment Rupert is boxed.

Lachlan has a checkered history of business leadership and deal making. He appears to share his father’s right-wing views, although one gets the sense he is neither as involved nor as astute about politics. Nor does he share the paternal passion for news and newsprint. He does not appear to read books.

He was exposed to books. There were some in the eighteenth-century Chippendale bookcases in the Upper East Side penthouse in which he was raised. But he seems not to have troubled them and he admits to not opening many in university—he was into rock climbing. In 2008, he wrote a short foreword to Dead Lucky, a memoir by the climber Lincoln Hall. That seems to be the extent of his engagement with literature, although he does appreciate books as brand extensions for Fox News personalities:

I always use the example of when our Fox News hosts write books, and they are books from history books to political books to cookbooks, they shoot to the top of The New York Times best seller lists. And so clearly, our audience is engaged with us not just around the breaking news of the day or the opinion in prime time, but really about . . . they have an emotional engagement to the Fox brand in a much richer and more important way. And that’s an engagement we can do much more with… [and] monetize more efficiently.

It’s not like his father loved books, either. I’ve often wondered why Rupert bothered with HarperCollins. I’ve read several biographies of him and there’s never a sense that he feels for books what he feels for newspapers. And he can’t be owning HarperCollins for its financial performance. The company has been inert for the last decade, refusing to grow, producing about 20 percent of News Corp revenues (equally inert), year in and year out. The billion worth of bolt-ons (Houghton Mifflin and Harlequin) have done nothing but help it stand still, much like expensive acquisitions at Penguin Random House.

The best answer I can come up with is that Rupert likes the particular kind of social capital that comes with owning a book publisher. He probably gets a higher volume of social capital from owning newspapers and television assets, but books matter to people at the smarter end of the media spectrum and Rupert likes to matter to them.

Lachlan isn’t wired that way. Like a lot of billionaires’ kids, he takes for granted that he matters. I suspect he looks at HarperCollins as a waste of capital. It’s not contributing to the growth of the empire. There is no bold future ahead of it. It just sits there. If Paramount could unload Simon & Schuster for $1.6 billion this year, HarperCollins, at more than twice the size, ought to command north of $3 billion. That’s money that could be put to productive use. More digital real estate assets. Maybe sports betting. The next Myspace. (Checkered, remember.)

Rupert raised his kids to think of themselves as builders, deal makers, and media visionaries—like the kids on Succession. There are real questions about whether the kids are up to the job and can keep from stabbing each other in the eye—also like the kids on Succession. About the only thing we can say for sure is that they’ll feel compelled to do something with their inheritance once out of Rupert’s shadow. And so HarperCollins takes its first step into an uncertain future.

If you watched Succession, a corporate tragicomedy built around a wealthy media family not unlike the Murdochs, you might have wondered if the people who own and operate Fox and New Corp are as assholic as the characters on screen. My experience publishing the Lachlan Murdoch book suggests yes.

The author, Paddy Manning, had spoken to some Murdoch minions while reporting his book. He mentioned to them just as it was going to press that the manuscript contained a paragraph thanking them for their assistance to his reporting. They went ballistic. They thought they’d been operating off the record. Manning’s Australian publisher soon received a lengthy letter from a prominent Australian “reputational risk lawyer” threatening to go to court to prevent publication of the book if the expression of gratitude was not removed. I’m pretty sure they’d only needed to ask nicely to get it removed, but assholes be assholes.

As the North American publisher of the book, Sutherland House received a similar letter. Not billing by the hour, I returned a brief note informing them that “the paragraph to which you refer is not in my edition of the book.” We’d cut it last minute at Manning’s request.

I thought my note had been clear, but it seemed to baffle the learned counsel of the Murdoch minions. A longer, more quarrelsome letter followed, this one demanding to know if the paragraph to which I referred (the only one either of us had cited) was the same paragraph in the highlighted passage in the attachment of the previous letter sent on whatever specific date: “Mr. Whyte’s representation causes my clients consternation given the ambiguity arising from its brevity.”

Learned counsel went on to demand that I inform them in excruciating detail of the printing and distribution arrangements for our book and how we planned to have returned and destroyed any copies that might have been printed with the offending expression of gratitude, etc.

Not satisfied with bombarding us with legal paper from the other side of the globe, Murdoch’s minions hired an additional platoon of lawyers from what I used to consider a respectable Toronto firm, McCarthy Tetrault LLP. They applied some heat of their own in an obstreperous letter, the subject line of which was “Proposed Book Release,” as though we required the firm’s permission. Like the Australian lawyer’s letter, it was labelled “urgent and not for publication—private and confidential.”

Not billing by the hour, I answered again in laconic fashion: “Hello—I have given a satisfactory answer to your original question. I stand by it and I consider us to be on the record in all of this correspondence.” I’d added the last line—bullies tend not to want their bullying exposed—after consulting with Julian Porter, QC, a good friend and the dean of Canadian libel lawyers. I also copied my reply to Julian.

The next missive from McCarthy Tetrault was almost civilized. “My view is that it might be productive to have a brief without prejudice (that is, off the record) discussion at your convenience today.” Julian took it from there, explaining to McCarthy Tetrault, the Australian reputational risk sharks, and Murdoch’s minions, that they needed to piss off. And they did.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

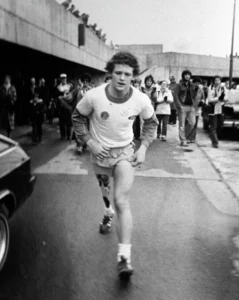

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )