Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

Bill Vigars, author of Terry & Me, published a piece for the Globe and Mail. Read it here.

Bill Vigars was the director of public relations and fundraising for the Canadian Cancer Society. He is the author of Terry & Me: The Inside Story of the Marathon of Hope, from which this essay has been adapted.

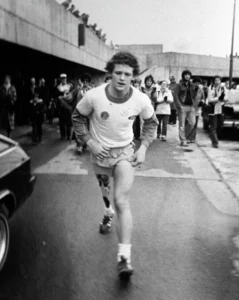

When Terry Fox set out to run across Canada on his prosthetic leg to raise awareness and money for cancer research, he had support from the very top of the Canadian Cancer Society. Ron Calhoun, a General Motors executive and chairman of public relations and fundraising for the society at the national level, met with Terry and suggested that he call his run the Marathon of Hope, which was great branding. Ron also sent a short memo to the provincial chapters, alerting them to the run and asking for their support.

That explains how my boss at the time, Harry Rowlands, executive director of the Ontario chapter, showed up at my office door one day with a memo in his hand from the national office. I had joined the Ontario chapter as director of fundraising and public relations only weeks before. “There’s a young fellow, an amputee, running across Canada,” said Harry, a former Bell Canada executive. “He hopes to raise some funds for the society. See what you can do for him.” Apart from the fact that he was from British Columbia and running the equivalent of a marathon a day, we knew almost nothing else about Terry Fox.

I first met Terry in person outside of Edmundston, N.B., on June 9, 1980. I wanted to get to know him and his travelling companions – his brother Darrell and best friend Doug Alward – and plan for his eventual arrival in Ontario. He was 58 days into the Marathon of Hope at the time and he wasn’t very happy with the Canadian Cancer Society.

He had already run through most of Atlantic Canada, and along most of the route he’d passed anonymously and raised little money. Apart from a small flurry of news reports at the very beginning of the run, the media hadn’t demonstrated much interest in him. The Canadian Cancer Society’s Newfoundland and New Brunswick directors, Bill Strong and Stan Baker, had stepped up and done the best they could for him, but both were essentially one-man operations and they already had their hands full. Terry didn’t know this when he’d started out, but he had chosen a start date right in the middle of the Canadian Cancer Society’s biggest fundraiser of the year, the annual daffodil campaign.

Tens of thousands of Canadians volunteer for the daffodil campaign every year and millions of dollars are raised (in 2022 it was $6.8-million). The project requires the full attention of the senior people at the society and its provincial chapters. Perhaps that explains why the Canadian Cancer Society could not drop everything it was doing in the spring of 1980 to help some crazy kid with his cross-country run. It’s not that people weren’t unsympathetic or unappreciative. They were just busy with something that to their minds was much bigger: their key fundraiser of the year and a proven winner. Terry was entirely unproven and as far as anyone could see, probably a one-off event – was he going to run across Canada again the next year?

And while Terry had the support of Ron Calhoun at the very top of the Canadian Cancer Society, that wasn’t worth as much as it seemed. The society is a bottom-up, volunteer-led organization. The national leaders can’t dictate priorities to the provincial leaders, who can’t dictate priorities to the district level. The memo that had gone out from national headquarters to the provincial chapters asking that we support Terry was a request, not an order. The national office wasn’t in a position to offer Terry any support on the road or funding of any kind.

Oblivious to these realities, but knowing that he was falling short of his fundraising potential, Terry poured his frustrations into the diary he kept through his run.

“I started to try to do whatever I could to let the Cancer Society know about that potential. I tried to let them know as best I could that I was dependent on them to have things prepared and set up before I got there. In some places they did it; in some places, they didn’t. It was frustrating for me because I knew there was not only money not being raised but people who I could have inspired, people who could have learned something, were missing me and that was because of the Cancer Society.”

I spent a few days with Terry in New Brunswick and watched him get up at 4 a.m., climb into the donated Ford van, and begin running on the shoulder of the highway at 5 a.m. in the pitch dark. I saw him run all day long, looking strong and determined yet somehow fragile when the 18-wheelers rumbled past him, until he’d clocked his 26 miles. And I saw him wake up the next morning and do it all over again. I was deeply impressed at the way he interacted with people along his route and how he spoke sincerely and powerfully to small informal gatherings in the towns he passed, telling them about the kids he’d met in the cancer ward back home and his determination to help find a cure. I came away in awe of him and determined that the Ontario chapter would promote him to the moon.

But I knew he had a long way to go before he reached the Ontario border. He had to run clear through Quebec first, and he was probably going to get even less support there than he had in Atlantic Canada. He didn’t speak French and the Quebec chapter had other priorities. I didn’t have jurisdiction to work with him in Quebec. I told him not to get discouraged and that we’d have a lot going for him by the time he reached Ontario.

It was a bit of a bluff on my part. Ontario hadn’t committed to anything yet and it was not at all clear that it would.

The Canadian Cancer Society hadn’t dealt with anyone like Terry Fox before. He’s what we now call a disruptor. He had his own vision. He was working outside the usual channels to pursue his self-determined goals and, in the process, he was inventing a whole new approach to fundraising for cancer research. Instead of volunteers going door to door with pots of flowers, he was saying “Come to Terry.” His method was new: untried, untested and untrusted by many in the society who were comfortable with its traditional, time-honoured approaches to fundraising.

I hadn’t been at the Canadian Cancer Society long enough to be deeply invested in the old ways of doing things or to fear change. In fact, I’d been hired to shake things up a bit. And I’d had the advantage of having spent time with Terry. I’d seen him in action. I’d felt his commitment. I knew how he moved people. I was genuinely caught up in the unique brand of excitement he generated. I was convinced that if we could just get Canadians to see him and hear his message, something special would happen.

But first we had to get Ontario onside. The provincial division is further divided into eight districts: Ottawa, Eastern Ontario, Toronto, Oakville/Mississauga, Hamilton/Niagara, Southern Ontario, Central Ontario and Northern Ontario. From the outset, Toronto and Hamilton did not want to be part of the Marathon of Hope. Given that they were the two biggest districts in Ontario, this was a major stumbling block.

The dissenting districts argued that the April daffodil campaign had just finished and they did not have the volunteer manpower available to mount another major project. One local office told us, “we’ll be on holidays.” I explained over and over again that the Marathon of Hope was going to be unlike anything they’d seen before. They were unmoved. I got the sense that some of the district directors simply didn’t want to take on more work or responsibility.

Despite the lack of alignment, those of us who believed in the Marathon of Hope forged ahead. Terry was approaching at the rate of 26 miles a day and we had a million things to do in preparation. We couldn’t afford to waste time. We just hoped for the best and tried not to think about possibly having to tell Terry that the Canadian Cancer Society wasn’t going to get behind him in the nation’s largest province. We took comfort in the fact that district directors in Ottawa, Eastern Ontario, Southern Ontario, Central Ontario and Northern Ontario were behind us. We might be without the two largest districts, but we at least had majority support.

Otherwise, things were going well. I was collecting positive news to share with Terry. Toronto Maple Leafs star Darryl Sittler was going to meet him and we’d lined up a Toronto Blue Jays game for him and a visit to the CN Tower – items that he’d mentioned were on his bucket list. Things were falling into place. I felt confident that we’d be able to do almost anything Terry wanted.

And then came the crisis call. John Simpson, the Canadian Cancer Society’s audio-visual consultant, had decided to invest his own money to follow Terry with a cameraman, Scott Hamilton, and various sound technicians. Way back in Nova Scotia, they had started shooting footage for a documentary. They picked up with Terry again in Quebec City, which was where he called from. John’s message was short and blunt: Terry, Doug, and Darrell had run out of money. They had also used up their gas cards. All of them had colds and they had been eating poorly and sleeping every night in the cramped and smelly Ford Econovan. John had just used his own credit card to put them up in a motel. “If you don’t do something fast,” he said, “this thing is not going to last another week.”

Things got worse. The next morning, the Quebec Provincial Police took Terry off the main highways and told him if he did not have a “Slow-Runner Ahead” sign installed on the back of the van, he was off the road completely.

I immediately called one of my bosses, Ron Potter, the volunteer chair of publicity and fundraising for the Ontario division. Ron was an insurance executive in London, Ont., and a former football coach at the University of Western Ontario. He was a wise and good-humoured man with natural leadership abilities. I explained the problems and he drove into Toronto first thing Monday morning. As he was driving, I met my other boss, Harry Rowlands, at his office door and brought him up to speed. By 10 a.m., the three of us were together in Harry’s office. What the hell were we going to do?

Harry had a sly smile on his face and a solution. “Well, technically you can’t go into Quebec to help. It’s a different division. But if you want to take a vacation, you can do anything you want.”

I mentioned that having just taken the job, I hadn’t accrued many vacation days.

“You have to do what you have to do,” Harry said.

So I did.

My assistant, Deborah, called a sign company and ordered a round metal sign to fit over the spare tire on the van’s rear door. It would be ready late Wednesday night.

I was ready to head to Quebec, but before I left there was a big decision to be made – one being deliberated way over my head. Ron Potter and another key publicity volunteer, Rick Hamilton, a radio DJ in Windsor, had called an emergency meeting of the Ontario publicity and fundraising committees, pulling volunteers from across the province into Toronto on 48-hours’ notice. The topic under discussion: was Ontario in or out of the Marathon of Hope?

About 40 people arrived from all over Ontario and gathered in a meeting room at the Westbury Hotel on Yonge Street near Maple Leaf Gardens. At the time, it was one of the largest and nicest establishments in the city. Harry, as the senior staff member in attendance, said nothing. He worked for the volunteers, not the other way around, although I suspect he had made his opinion known quietly to a number of trusted people beforehand. Ron chaired the meeting. He, too, said very little. He let everyone else in the room express opinions. Representatives from the Toronto and Hamilton districts repeated their concerns about being overstretched and their reluctance to back the Marathon of Hope.

My stomach was in knots. There was so much riding on the decision. It would make or break Terry’s run. We would either be in a position to deliver everything I’d promised him and launch the Marathon of Hope into the stratosphere, or we’d be saying sorry, wishing him well, and maybe waving at him as he headed toward Manitoba. I couldn’t bear it.

After all the back and forth, Ron said his piece. He backed Terry vigorously. He spoke of Terry’s fundraising vision. He related all that he had heard of Terry, his personality and his level of commitment. He said he was ready to bet on the kid and that this was something the society just had to do.

The Hamilton representatives finally came around. The Toronto delegation, however, remained unmoved. A vote was called.

It passed, a huge turning point for the Marathon of Hope, not to mention for the Canadian Cancer Society, giving everything that flowed from it.

Harry turned, looked at me, and said, “Go!”

I spent the rest of the summer with Terry. The recurrence of his cancer kept him from completing the Marathon of Hope but he raised $24.17-million for cancer research in under one year. Since his passing in 1981, millions of people in Canada and around the world have participated in annual Terry Fox runs and close to $1-billion has been donated in his name.

Read on the Globe\’s Site.

More on \”Terry & Me\”

There has never been a Canadian quite like Terry Fox and there’s never been a story quite like The Marathon of Hope.

A twenty-two-year-old cancer survivor and amputee, Terry set out from St. John’s, Newfoundland in April 1980, aiming to run across Canada to raise money for cancer research. His first months on the road in Atlantic Canada and Quebec were not only physically taxing—he ran the equivalent of a marathon a day—but frustrating as Canadians were slow to recognize and support his endeavor.

That all changed when he met a young man named Bill Vigars, who on behalf of the Canadian Cancer Society led a campaign to ensure that every person in Canada knew the story of this outstanding young man. Vigars was by Fox’s side through all the highs and lows until the tragic end of his journey in Thunder Bay. A recurrence of his cancer cut short Terry’s dream and, soon, his life. Now, for the first time, Vigars tells the inside story of the Marathon of Hope—the logistical nightmares, boardroom battles, and moments of pure magic—while giving us a fresh, insightful portrait of one of the greatest Canadians who ever lived.

BILL VIGARS was the Director of Public Relations and Fundraising for the Canadian Cancer Society’s Ontario Division, and acted as Terry Fox’s public relations organizer, his close friend and confidante. He set up several key events as the Run entered Toronto.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )