Disappearing media

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

Sorry to post twice in a day but thanks to Chris Oliveros at the esteemed Drawn & Quarterly, we’ve identified mistakes in this morning’s newsletter. I was going to wait until next week to post a correction but thought it was best to do so promptly.

The Canada Book Fund does not consider books written by Francophone authors and published by a Quebec publisher to be eligible for the 1.33 multiplier. So Quebec-based Francophone publishers are not getting disproportionately more money from the Canada Book Fund because of the minority-language multiplier. That’s my mistake. Sincere apologies.

This doesn’t change the fact the Quebec publishers, the healthiest sector of the Canadian publishing scene, are getting four-times per capita what non-Quebec publishers are receiving. Nor the fact that the benefits of federal cultural policy fall overwhelming to Quebec. Nor the fact that it’s for political reasons.

The odd twist in all this is Phidal, the company with all the Disney books, is considered a minority-language publisher in Quebec. So long as its Disney and Barbie books are being “written” by Canadians, they’ll be eligible for the multiplier effect.

_______

Launched last fall, Sutherland Quarterly is a new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s best writers. Each essay will be published as a stand-alone book and sold at retail in the usual manner; the essays will also be available (at a preferred price) by annual subscription. Elaine Chin’s We Are Not Okay, the third edition in the series, hit stores earlier this month at $19.95 (plus HST); the subscription price is 20 percent off the cover price or $67.99 (including HST). I hope you’ll consider subscribing.

Two newsletters back, I presented a list of the top twenty English-language publishers based on data from the Canada Book Fund. What I didn’t present was the other, more interesting half of the story.

Of the $33 million that the Canada Book Fund distributes annually, more than half goes to Quebec-based publishers. At first, that didn’t strike me as problematic. The Canada Book Fund is all about building a better book publishing industry. It supports individual publishers on the basis of sales. There’s a formula: the more you sell, the bigger your grant. I thought Quebec’s disproportionate share was probably a result of its predominantly French-language publishers selling to a more-or-less captive French-language audience. They were doing well. Fill their boots.

Turns out, it’s a bit more complicated than that. The fine print of the Canada Book Fund reveals that it privileges minority-language publishers. For instance, the first $500,000 in sales at a minority-language publisher (and the vast majority of Quebec publishers are French-language publishers) are weighted 33 percent higher than the first $500,000 in sales at an English-language publisher.

Also, the Canada Book Fund gives equal weight to books authored by Canadians and books translated by Canadians. So if you look up TC Media Livres Inc., you’ll find a range of books by Quebec authors alongside French translations of international bestsellers such as Joel Bakan’s The Corporation, Carly Fiorina’s Hard Choices, Terry Burrows’ The Beatles, Bea Johnson’s Zero Waste, Dutch mindfulness guru Eline Snell’s Breathe, Hawaii-based Gary Kraftsow’s Yoga, and a bunch of titles from New Zealand children’s author Trace Moroney. In the literature section are translations of H. G. Wells, Oscar Wilde, Jules Verne, Poe, Shakespeare, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Jane Austen. TC Media Livres Inc. gets $648,000 annually from the fund, more than any single English-Canadian publishing house.

That’s how the Canada Book Fund’s granting formula and its eligibility rules favour Quebec-based, French-language publishers. That’s how the fund distributes $2 per capita in Quebec compared to .50 cents per capita in the rest of the country. Four times the support. (CORRECTION BELOW)

As far as Ottawa is concerned, this is a feature, not a bug. All of our cultural support programs are similarly lopsided.

The Canada Council for the Arts spends $141 million in Quebec or $16 per capita. It spends $310 million in the rest of Canada, or $10.50 per capita. The prairie provinces, with 80 percent of Quebec’s population, get 38 percent of Quebec’s funding, which on a per capita basis means a resident of Quebec gets $2 for every $1 someone living on the prairies receives.

The CBC spends $816 million on its French-language services to the 8.2 million Canadians for Franco-Canadians, or $99.5 per capita. It spends $1.1 billion or $38 per capita on Canadians who speak English as the first official language. That’s two-and-a-half times more per capita for Francophones.

There is a reasonable argument to be made for allowing under-represented groups greater access to cultural funding. It’s quite clear from the Canada Book Fund’s data, however, that Francophones are not under represented on the Canadian publishing scene. There are a disproportionate number of them and they are disproportionately successful. It is English-Canadian book publishing that is in serious danger of disappearing.

While it would be hard to argue that Anglo publishers should get a greater share of the pie and Francophone publishers less, it makes eminent sense to bring the Anglos up to the same level of funding as their Francophone brethren.

Obviously, language differences make Quebec and the rest of Canada distinct markets, but there is also a strong suggestion in the data that the Canada Book Fund is a major reason why Quebec has four times the publishers per capita that English Canada maintains.

The Canada Book Fund is the best designed tool in the federal policy kit. Unlike the Canada Council, with its disincentives to commercial viability, the book fund encourages publishers to produce commercially viable books and work harder at marketing them, and it rewards them when they succeed. At full strength, it helps build a stronger industry, like the one Quebec has.

If the numbers I’ve mentioned above were reversed, the Quebec publishing and authors lobbyists would be at the barricades. It’s baffling to me that Ottawa’s meanness towards arts and culture in English Canada isn’t a political issue. Lobbyists on behalf of our representatives—The Writers Union of Canada and the Association of Canadian Publishers—make polite submissions through official channels and weep in a corner when a relative pittance comes their way. A new militancy is warranted.

The underlying problem is that cultural funding in Canada has been thoroughly politicized. It was an invention of the Liberal Party of Canada back in the last century, and it continues largely as Liberal project today (the Conservatives are a whole other problem which I discussed here). The highest political necessity of the Liberal party is to maintain its base in Quebec, without which winning federal elections is impossible. Cultural funding is one of the major ways that the Liberals maintain support in Quebec.

It is astonishing how far this Liberal government (one famous for not doing much of anything) will go to appease Quebec culture. Melanie Joly was the Liberal Minister of Canadian Heritage, the department that oversees cultural programs, from 2015 to 2018. She spent most of her time in the portfolio talking about how the government’s approach to arts and cultural support was “broken.” She noted that it was designed to protect Canadian cultural producers and distributors from competition with the rest of the world when it should have been recognizing that in the age of the Internet, culture is global. People want access to the best books, TV shows, movies, music out there, regardless of country of origin, she said, so the best way to help Canadian writers, filmmakers, musicians, and artists in such an environment is to help them find their global audiences.

Joly wanted to shift the historic focus of our cultural policy from Canadian content quotas and other outmoded forms of protection to promotion of Canada’s arts and culture to the rest of the world. Irene Berkowitz, then a cultural policy expert at Toronto Metropolitan University, rightly congratulated her for finally recognizing that we were no longer living in an analog world and that Canadian artists and producers have the capacity to compete in an increasingly digital, borderless, cultural marketplace.

Unfortunately, Joly’s new direction did not fly in Quebec. She announced that she had done a deal with Netflix that would result in Netflix building its first studio outside the US with $500 million production budget for Canadian film and TV over five years. Quebec TV and film people hated the deal because it did not have a specific guarantee for French-language content. It became a huge issue in the province. Joly was mocked on the popular talk show Tout le monde en parle and Quebec sentiment coalesced around the notion of taxing Netflix to pay for more French-language content.

The Trudeau government, sensitive as ever to its Quebec base, promptly bounced Joly from the Heritage portfolio and handed it over to two other Quebec ministers, first Steven Guilbeault, then Pablo Rodriguez. Together they have overseen a complete reversal of the Joly doctrine. Instead of embracing the opportunity to find new audiences for Canadian content around the world, they brought in two new bills: Bill C-11, the Online Streaming Act, designed to apply all those outdated CanCon rules that applied for decades at CTV, CBC, and your local radio station to the likes of Netflix, Prime Video, Disney+, YouTube and TikTok; and Bill C-18, which effectively intends to tax the sharing of and links to Canadian news on Facebook and Google in order to support our failing conventional news businesses, including newspapers and broadcast networks.

Where Joly was headed was something like South Korea’s cultural strategy which has been to develop highly successful, exportable television, film, music and literary properties. They’re winning Best Picture Oscars, developing an endless stream of fresh TV shows that get picked up by the big platforms, changing the sound of the world through K-pop, and starting to assume a major presence on the literary scene.

Canada unquestionably has the talent to do the same, but most of that talent is now produced or published outside the country. That will continue to be the case. The reactionary, dirigiste cultural policy being pushed by Guilbeault-Rodroguez is designed to make the 1970s last forever and, more bizarrely, to drag the whole of the digital world back to Canada in the 1970s. The net result can only be that Canada’s presence on the cultural stage will shrink. We’ll prop up our old domestic industries for a few more years, prolong their deaths, frustrate theefforts of new things to rise in their place, and eventually leave the field barren.

At least, we will if English Canada continues to let Quebec protectionists drive the Canadian cultural agenda.

In closing, let me apologize if I sound dogmatic on these issues. I tend to feel warmly about them and I find it passing strange that they receive so little attention anywhere else. So I rant on. I don’t think I have all the answers. I do firmly believe that we—citizens, cultural industries, governments—have a lot of work to do. The intention is to provoke a conversation, not to have the last word. Comments are open.

The single biggest independent publishing company in Canada according to the Canada Book Fund data is Editions Phidal, which has an office in Montreal. It receives $750,000 annually from the Canada Book Fund, the only firm receiving more than TC Media, above. Ever heard of it? Neither had I.

Editions Phidal is a children’s publisher that that has the rights to produce story books, activity books, and sticker books for a wide range of Disney, Pixar, Mattel, and Nickelodeon brands. It also publishes children’s versions of classic stories, from Robinson Crusoe to The Ugly Duckling.

The best I can learn from what little there is on the Internet about Editions Phidal, is that it was founded by a Montrealer, Albert Soussan, in the late 1970s, and that it gained access to a bunch of Disney characters in the 1980s.

Albert now gives his address as Miami, where Phidal has an office, as does David Soussan, VP sales at Phidal. There are at least two other Soussans working for Phidal in Montreal: Lionel, production manager, and Karen, the company’s lawyer. I’m guessing David, Lionel, and Karen, are children?

One presumes the Soussans have figured out how to meet the Canada Book Fund’s requirement that the company be 75 percent Canadian owned while decamping to Florida.

And I’m further guessing that a Barbie or Lion King or a Mulan children’s book is eligible for the Canada Book Fund so long as it is “original,” the usual length for a children’s book, and authored by a Canadian. I’m not sure this is what Phidal is up to—it does not make author or translator names visible on its website—but I can’t otherwise make sense of the level of support it receives.

I’m not suggesting malfeasance here. What Phidal does may be the opposite of “telling our stories to ourselves”—the traditional rationale for government support of the arts in Canada—but one has to presume the company is playing by the rules. The Canada Book Fund is quite diligent about enforcing them.

Also, it’s a seldom acknowledged truth about Canadian independent publishing that the children’s publishers are by far the strongest part of the sector and almost all of them rely heavily on making unidentifiably Canadian books to foreign markets, particularly the US. The same is true of the bigger English-Canadian independent houses. ECW and Greystone are making a lot if not most of their money selling Canadian-authored or Canadian-translated nonfiction books on non-Canadian subjects to international audiences. I have no problem whatsoever with this being part of what we do as Canadian publishers. Unfortunately, it’s fast becoming all that we do.

So here’s another policy area we have to work on. We have government programs that promote literary art, and government programs that promote the building of a publishing industry, but we don’t have individual or coordinated government programs that simultaneously support the building of an industry and the telling of Canadian stories to Canadians by Canadians. There has to be a betterway.

CORRECTION: Thanks to Chris Oliveros at the esteemed Drawn & Quarterly, we’ve identified mistakes in this newsletter. I was going to wait until next week to post a correction but thought it was best to do so promptly.

The Canada Book Fund does not consider books written by Francophone authors and published by a Quebec publisher to be eligible for the 1.33 multiplier. So Quebec-based Francophone publishers are not getting disproportionately more money from the Canada Book Fund because of the minority-language multiplier. That’s my mistake. Sincere apologies.

This doesn’t change the fact the Quebec publishers, the healthiest sector of the Canadian publishing scene, are getting four-times per capita what non-Quebec publishers are receiving. Nor the fact that the benefits of federal cultural policy fall overwhelming to Quebec. Nor the fact that it’s for political reasons.

The odd twist in all this is Phidal, the company with all the Disney books, is considered a minority-language publisher in Quebec. So long as its Disney and Barbie books are being “written” by Canadians, they’ll get the multiplier effect.

Our regular reminder to readers to support independent booksellers. Click this link to make the above map come alive.

This is the 199th edition of SHuSH, the official newsletter of the Sutherland House Inc.

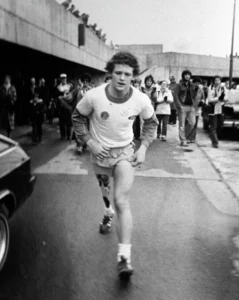

There was an interesting piece in the New York Times a week or so ago about James Daunt (above), the incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, the most important bookstore chain in the English-speaking world. It didn’t quite get to the nub of the matter. Barnes & Noble has

The world of non-fiction from Sutherland House ( and Beyond )